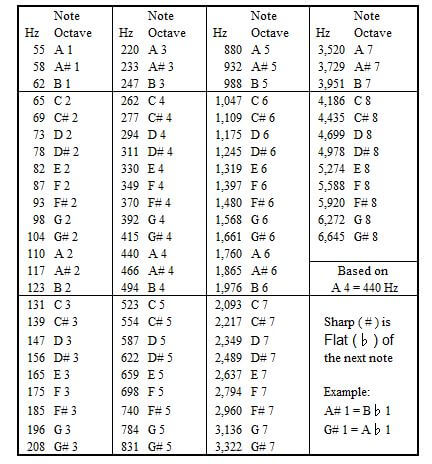

Octave is the musical term for doubling the anchoring frequency. This is do, re, mi … back to do. If you start at a 55 Hz A1 (A1 = the note A in the first octave) that second “do” will be A2 (A in the second octave) at 110 Hz. As your octave number increases so does the pitch, higher and higher. The next doubling brings you to the third octave, fourth and so on (A3 = 220 Hz, A4= 440 Hz). What can be confusing to people is that they think they want a singing bowl with a note of B without realizing there are many B notes that sound entirely different – each one in a higher or lower octave. All the sound bowl notes appear in multiple octaves, each with a different frequency. So when you say “I want a B note bowl” it is incomplete information. It is like saying I want chocolate ice cream – do you want a spoonful, a cup, a gallon, or a truckload?

What is a Bowl’s Main Tone?

Singing bowls are complex, the wonder of their sound is rooted in the many tones you hear at once. The primary singing bowl tone is the deepest one you first hear when you strike it with a mallet. Typically this is the strongest tone in a bowl, however some bowls are overtone centric and the next highest note is most prominent. Nonetheless if you arrange a group of bowls together you will be able to tell lower and higher regardless of how strong the overtones are, your brain is tuned to making this differentiation. That low singing bowl note is commonly called the primary tone or the “fundamental” though deepest or main tone is another way it is described. First partial is the technical term used my musicians and scientists to describe the fundamental tone. The deepest antique singing bowl I’ve measured has been a B in the first octave, and the highest goes well into the sixth octave, over 1000 Hz. All antique bronze singing bowls have multiple tones in addition to the fundamental. These are called overtones or second, third etc. partial.

Perfect Pitch

Perfect or concert pitch is a single point in the spectrum of tones that comprise a note. Musicians hear this spectrum in terms of “in tune” or perfect, sharp, and flat. A sharp note has a slightly higher pitch than the perfect note, a flat slightly lower. For an even finer distinction musicians divide each note in the musical scale into 100 musical cents – 50 sharp and 50 flat. It is a rare person who can hear the difference of one musical cent. Perfect pitch then is defined as a range of very slightly different sounds in the center of the full range of tones for a given note.

If you allow for the limits of most ears then the middle 20% of a note – plus or minus ten musical cents from absolute center will qualify as perfect or true tone. A musician with trained hearing might argue for a tighter standard. Many people would still not be able to tell with a loser standard.

Since nobody in the Himalayas ever made one of these bowls with the Western music scale in mind it is rare to find one that is exactly top dead center of the singing bowl note it is closest to. For the most part, singing bowl pitches are above or below the exact note, pretty evenly distributed between sharp and flat. Statistically, then , only 1% or the one cent in a hundred will have the absolutely perfect or concert pitch and about 20% will have the more generous range commonly used.

Perfect Pitch and Pitch Memory

Perfect pitch also refers to a skill some people have that allows them to hear a sound and determine whether it is an exact note or not (which makes them a natural at tuning instruments). It also means they can hear a sound and translate it, say which note and octave it is. Most authorities believe perfect pitch is something learned easily as a baby and by the time a child is 4 or 5 it can no longer be learned.

Pitch memory refers to a learned skill that allows a musician to hold a pitch in memory and then repeat that pitch. We all have some level of pitch memory, remember favorite songs for instance. Pitch memory can be improved with practice, unlike perfect pitch which is either there or not. I use the skill of pitch memory in assembling sets. Holding multiple singing bowl tones means I can pick bowls that bridge between those tones quite exactly. It is actually a lot of fun, finding that perfect bowl for a smooth progression.

Pegging Octaves 432 440 448 Hz

To make things a little more complicated, just like perfect pitch is has room for interpretation octaves can be set according to different criterion. The “A” note above middle C is used to peg or anchor the octaves. Once you set that A all the other notes are defined with mathematical precision. In Western music and the example I used at the top of this page 55, 110, 220, 440, 880 etc tare he frequencies assigned the note A when the perfect “A” is 440 Hz.

Not everybody and every time agrees that 440 is the right number. It is thought that the classical composers did not write to exactly 440 Hz. Some people believe that a flatter central note of 432 Hz has a more natural sound. The effect of changing “A” is to move perfect pitch for each note to a different range. That is right, every note changes, what is flat or out of tune at 440 is perfect at 432. 448 Hz is the most common sharp or bright variant of A440. Again, I only use what you mostly hear in the world, A440 to define tones.